Who among us has never heard of legendary titles like Max Payne, Half-Life, or Prince of Persia? Even gamers born in the 2000s will be familiar with these, either from hearing about them from their friends, seeing them in gaming compilations, or playing the classics themselves. And while the years have gone by, these games are still played today, sometimes out of nostalgia, sometimes by parents introducing them to their children. In this article, we’re going to take a look at why remasters are becoming more and more relevant nowadays before examining the challenges they pose for localizers.

Why Are Games Remastered?

Technology is developing faster and faster with each passing year. Graphics and game engines are becoming more realistic, and iconic new games are being released for today’s generation of players. The old Lara Croft and Max Payne hardly compare to modern titles like The Last of Us or Red Dead Redemption 2.

But nostalgia is a powerful thing, which is why we’d like to take a trip down memory lane to relive the joy we felt experiencing these titles for the first time. There’s just one problem. Modern gamers often struggle to play old games like these. The solution? Remasters. Remasters breathe new life into the classics, preserving the atmosphere of the original while bringing it in line with modern standards and expectations.

The Technical Side of Remasters

It should come as little surprise that the main reason games from the 2000s receive remasters is to update the graphics and overall visuals. Modern gamers are used to high standards, with photorealistic models, smooth animations, gorgeous special effects, and 4K or even 8K support. By comparison, the original Max Payne and Prince of Persia: Warrior Within look a little wooden, to put it lightly. The models are boxy, the shadows are primitive, facial expressions and gestures are limited, and the same backgrounds are used again and again. All of these things shatter player immersion and are a far cry from what we expect to see in the 2020s.

Remasters solve this problem. The developers redraw textures, update models, adapt the interface for larger screens, and add new visual effects. Sometimes, the lighting and style are even changed to bring the game closer to modern cinematic standards. This gives players the opportunity to re-experience plots and mechanics in a new, modern light, one that doesn’t hurt their eyes or make them feel like they’re looking into a time capsule.

At the same time, improved graphics are what reel in a new audience, because they tend to appeal more to younger gamers who may never have experienced the original. A high-quality localization can then reinforce that interest. It makes the plot and characters more alive and relatable for a new audience while still appealing to gaming veterans’ nostalgia.

Linguistic Challenges

One of the first issues developers and localizers run into when remastering a cult game is the language. Professional game localization wasn’t really a thing in the 2000s, so games tended to be translated by fans or pirate studios. This led to the now infamous fan dubs and subs that had nothing to do with the original texts.

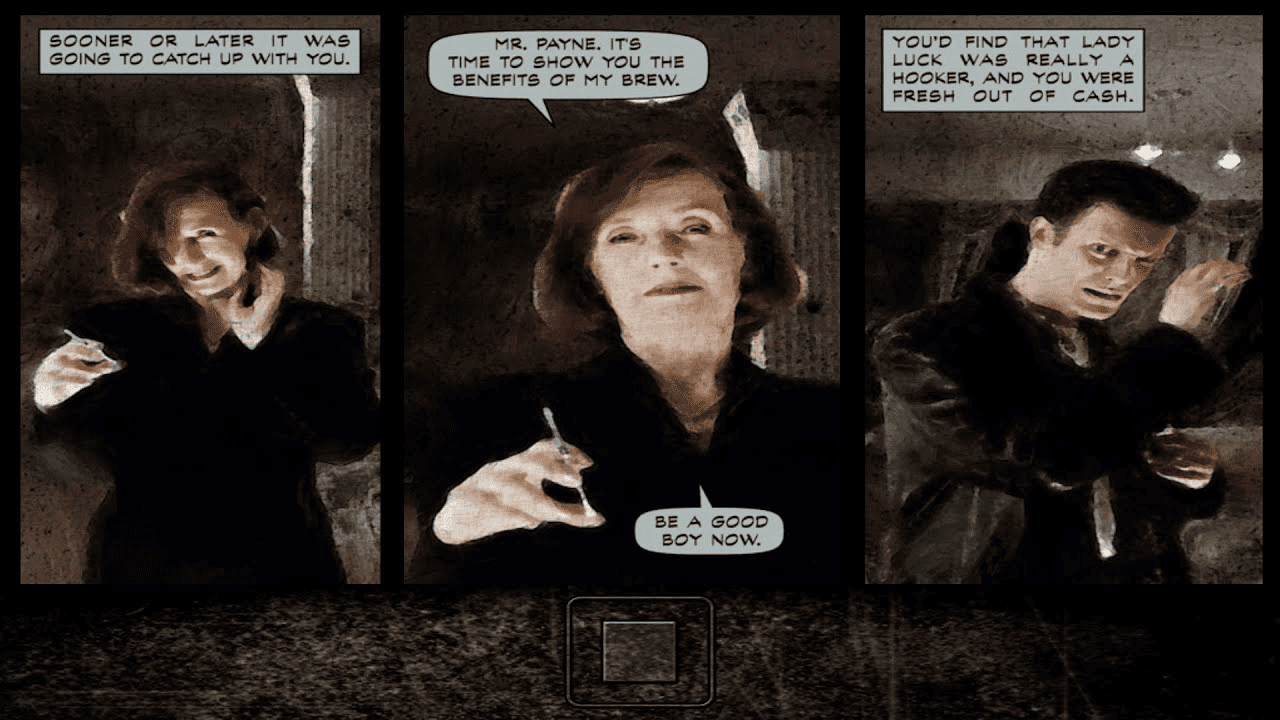

Max Payne

The legendary first installment in the Max Payne series is an excellent example of this. It has several fan translations, and every gamer from that time remembers “their” version. The issue is that most of these adaptations were littered with English calques and literal translations. The plodding, unnatural translation clashed with the dark noir narrative.

Old translations were full of stiff dialogue like “He cast a contemptuous look at me,” not at all what you would expect to hear from a fast-paced action noir. A more natural translation like “He looked like he was itching to blow my brains out” would work far better. The meaning is the same, but this replaces the Dickensian feel of the previous translation with some Blockbuster flair.

The German localization of Max Payne long struggled with text overload. Take “Lady Luck is a bitch, and I was fresh out of cash,” for example. First, it was translated as “Die Glücksgöttin ist eine gemeine Hure, und ich war pleite.” Literal, crude, and plodding. This was later changed to something with a little more oomph: “Lady Luck hatte mich verlassen, und ich war pleite.” This preserves the meaning, but sounds much more cinematic.

Some translations were so hilariously absurd that they became iconic. The Russian version of “Lady Luck was really a hooker, and you were fresh out of cash” was “Lady Luck is just a common prostitute, and you’ve run out of cash.” This line became very popular in fan communities and memes at the beginning of the 2000s, which was why it was kept in the remaster even though it clashed with the original.

Screenshot from Max Payne (2001). Source.

Modern localizers’ main task is to strike a balance. On the one hand, they must be wary of modernizing a game so much that it becomes unrecognizable to fans of the original. But on the other hand, they can’t just leave a calque in a game in 2025. The goal is to reach a compromise that will leave both the linguist and the player happy, and this requires great care and extensive collaboration with fan communities.

Half-Life 2

A lot of terms in Half-Life 2 were translated far too literally. For example, “Combine Overwatch” was first rendered as Kombinat Überwachung. “Combine” here refers to soldiers, whereas the German Kombinat is used for industrial enterprises. This is less of a calque, and more of a mistranslation—the soldiers have been turned into a factory. It didn’t take long for German players to catch on, and fans offered another option: Kombine-Sicherheit (Combine Security) or even just Combine, which better conveys the spirit of the original.

Combine Overwatch from Half-Life 2. Source.

Mistakes like these give a text a foreign air, detract from the atmosphere, and break player immersion.

Deus Eх

Another example is the cult RPG Deus Ex, a game which blends complex lore with social, political, and philosophical commentary. One character’s name was translated into Russian as “Джейми” (/ˈdʒeɪmi/, with a soft “j” sound [dʒ] and a diphthong [eɪ]), following Anglo-Saxon conventions.However, this was a mistake, as the correct transliteration of this Latin American name would have been “Хайме” (/ˈxaime/, where the “j” is pronounced like the “ch” in the Scottish word “loch.”The first vowel is a different diphthong [ai] and the stress is on the first syllable). Gamers in the 2000s grew used to “Джейми,” which may lead to issues in the remaster. Should professional correctness take priority over nostalgia? Should the mistake be fixed, or should the original version be maintained for fans?

Jaime Reyes from Deus Ex. Source.

Good re-releases respect the phrases and names that gamers have already accepted and fallen in love with. Remasters are made first and foremost for the players, after all. Preserving their emotional connection with the game is more important than adjusting the text to fit the rules. Maintaining the old translation is a way of paying respect to fan communities and is also a smart instance of fan service.

Localizing the Interface

Another important task is localizing the interfaces and quests of games from the 2000s. Here are a few examples that illustrate when changes are necessary:

- Save game → Spiel speichern

This translation sounds dry and unnatural. Today, we’re far more likely to see something like Fortschritt spiechern (Save progress) or even just Speichern (Save). These are simpler, more relatable to the player, and—most importantly of all—a common sight in modern interfaces. - Game Over → Spiel vorbei

While this was once a standard translation, it now comes across as needlessly formal. A more appropriate option for a modern remaster would be Ende des Spiels (End of game). Game Over could also be a nice nod to tradition, as it has long since reached meme status and become a part of gamer slang. - New game → Neues Spiel

This is technically correct, but it’s very dry. We’re far more likely to come across Neu starten (Restart) in modern interfaces, as it sounds friendlier and more natural.

Things like this seem trivial, but they shape a player’s impression of the game. In 2025, gamers don’t just expect updated graphics from a remaster, but also updated, modern language with more personality. Updating the interface is far easier, as there are unlikely to be disagreements with the fan community. The game menu is a universal tool, and any linguistic changes made for the sake of translation accuracy are normally for the better.

Cultural References and Jokes

Remasters should be adapted culturally to fit the times. Translators in the 2000s could afford to use student jokes and local memes, but a similar approach nowadays risks appearing outdated and immersion-breaking. Localizers must consider that modern audiences perceive language and humor differently. It’s important to find a balance between respecting the time period of the original and the modern day. This means that some phrases and references should be maintained for nostalgia’s sake, while others should be updated to ensure the text fits the cultural context of the 2020s. It is this flexible, sensitive approach to change that pushes remasters beyond mere restorations to make them feel alive and relevant in the modern day.

Mafia: The City of Lost Heaven (2002)

Games like Gothic II and Mafia: The City of Lost Heaven were packed with local jokes and references to their time. The original Russian localization of Mafia: The City of Lost Heaven (2002) had lines that were very much a product of the early 2000s, with mobsters often using expressions like “Ты чё, офигел?” (You trippin’?) or “Не гони пургу” (Don’t give me that shit).

Dialogue like this may have added flavor, but it certainly didn’t convey the atmosphere of 1930s Chicago. The Mafia: Definitive Edition (2020) remaster saw localizers move away from the streets in favor of a style more reminiscent of Hollywood Mafia films, with lines such as “Ты что творишь?” (The hell ya doin’?) and “Не морочь мне голову” (Don’t play games with me). This preserves the atmosphere of the time period and makes the game feel more cinematic.

The German version did a similar thing. The old 2002 translation included lines such as “Ey, spinnst du, oder was?” (Are you for real?), a very informal expression. This was changed to “Was soll das, Tommy?” (What the hell, Tommy?) in the remaster, a neutral cinematic version that doesn’t use more modern slang. This approach lent the game a sense of cohesion and preserved the authenticity of the era.

Screenshot from Mafia 2: Definitive Edition (Source, Mafia: Definitive Edition walkthrough Part 2: What a Crazy life!)

Reselling a Classic

Remasters aren’t just about updated graphics and improved localizations—they’re also repackaged games for a modern audience. Games in the early 2000s were released on disks and advertised in newspapers and on television, while digital platforms, stores, social media, and streaming services are the main channels of promotion nowadays.

Remasters therefore require close collaboration between translators and marketing editors. Marketing editors help to adapt the description, slogans, and promotional material for a new audience. For example, a slogan that worked well in 2005 could sound dated in 2025. “Ready to own the streets” and “Own the streets” were phrases used in promotional materials for the Need for Speed series that conveyed the idea of fighting on city streets. Marketing campaigns at that time frequently used the concept of the “street” as an image (the city, graffiti, street culture, such as PSP campaigns and street art in 2005). Slogans like these could sound unnatural in 2025. The team’s task is to keep the spirit of the original but speak the language of the new generation of gamers.

Moreover, remasters come out on new platforms, like the Nintendo Switch and the PlayStation 5, and marketing materials must be designed to fit the platform. Texts must be compact, engaging, and optimized for stores. The localizer and marketing editor work together to convey meaning accurately while ensuring the game appeals to both old and new players.

Final Fantasy VII Remake

Let’s take the German version of Final Fantasy VII Remake as an example. The original marketing materials in the late ’90s promised an “epic adventure with a state-of-the-art battle system.” For the remake, the marketing text was adapted to fit modern expectations, emphasizing cinematic visuals, an emotional story, and completely revamped combat. The same was done in the German version with “Ein episches Abenteuer neu geboren” (An epic adventure reborn), a modern description with a deferential nod to the original.

Resident Evil 2 Remake

The promotional materials in the late ’90s went all in on the horror aspect with “If the suspense doesn’t kill you, something else will!” In the remake, the marketing texts sound more modern and dynamic, with “A spine-chilling reimagining of a horror classic.” The German-language version emphasized the cinematography and atmosphere with “Erlebe den Horror neu” (Live the nightmare again). Nostalgia plays a significant role here. Few fans would pass up the chance to experience the atmosphere of their favorite games with upgraded graphics.

A New Audience for Old Hits

It’s also worth mentioning that remasters aren’t just for the fans—they’re also a chance to bring in a whole new audience. Younger gamers who’ve never played Max Payne, Gothic II, or the original Mafia see the games differently. A nostalgic approach won’t appeal to them, so these new products have to be capable of competing with modern hits. Remasters can’t just reproduce an old translation and call it a day—the language and cultural codes must be adapted to make them understandable and relatable to a new audience.

To do this, localizers and marketing editors use the tools of modern language, cinematic dialogue, memeable references, and easily recognizable techniques. When working on a remaster, it’s important to consider the expectations of a new audience who may be playing the game for the first time. There are several things to keep in mind to accomplish this:

- The language should be natural and engaging without any old-fashioned turns of phrase.

- Character dialogue should maintain the same charisma and personality, but also meet modern storytelling standards.

- Dialogue should be cinematic, with subtle pauses, implications, and quips.

- Excessively literal translations and calques should be avoided to make the language feel natural to gamers of the 2020s.

- A balance should be found between maintaining the atmosphere of the original and adapting it to fit new cultural norms.

In the 2000s, it wouldn’t have been unthinkable to hear lines such as “Ich gehe jetzt hinein und tue meine Pflicht“ (I will go inside and do my duty), but localizers today would choose more natural translations such as “Ich schau mal rein, keine Sorge“ (Don’t worry—I’ll go check it out). This conveys the same meaning, but it sounds far more engaging.

Screenshot from Final Fantasy VII Remake. Source.

In Final Fantasy VII Remake, the translators avoided old-fashioned dialogue like “Ich werde nicht zulassen, dass du das tust” (I won’t allow you to do that) in favor of more emotional lines like “Kommt nicht in Frage!” (I don’t think so!). This sounds more modern and dynamic.

Recommendations for Localizers

We can now see that a good remaster is always about striking a balance between the past and the present. Games from the 2000s have a unique atmosphere, and fans expect that to be maintained. At the same time, new audiences demand modern language, readable text, and relevant cultural references. With this in mind, localizers have to do more than just translate—they become a kind of mediator between different generations of gamers.

This is why it’s important to consider both the emotional value of old translations and new quality standards when creating a remaster.

Analyzing the Old Translation

Before getting to the adaptation, it’s important to examine the previous localization. Which choices were met with criticism? Which became iconic? Specific phrases may have been translated completely “incorrectly” but have now become standard and part of fan culture.

Target Audience Testing

No matter how good an adaptation is, it may not be taken well if it doesn’t align with gamer expectations. It’s important to bring potential points of contention up for discussion with the fan community through polls, focus groups, and pilot tests. This allows the team to figure out in advance where to keep nostalgic calques and where to replace them with more modern options.

Using a Hybrid Approach

The optimal choice for remasters is to strike a balance between maintaining the charm of the old localization and introducing more modern language. This allows new players to enjoy the game and gives veteran players the feeling that they’re being respected. This hybrid style is the best approach, as it unites different generations of gamers.

Working with Marketing Editors

Localizing a remaster isn’t only a question of translating the plot and dialogue—it also involves adapting the game for new platforms, new markets, and new audiences. It’s important to consider the marketing aspect, such as slogans, descriptions, and promotional materials. Working with marketing editors leads to a text that is both accurate and engaging for a wide audience, including gamers who know nothing about the original.